Yesterday, I released dabblet. One of its aspects that I took extra care of, is it’s keyboard navigation. I used many of the commonly established application shortcuts to navigate and perform actions in it. Some of these naturally collided with the native browser shortcuts and I got a few bug reports about that.

Actually, overriding the browser shortcuts was by design, and I’ll explain my point of view below.

Native apps use these shortcuts all the time. For example, I press Cmd+1,2,3 etc in Espresso to navigate through files in my project. People press F1 for help. And so on. These shortcuts are so ingrained in our (power users) minds and so useful that we thoroughly miss them when they’re not there. Every time I press Cmd+1 in an OSX app and I don’t go to the first tab, I’m distraught. However, in web apps, these shortcuts are taken by the browser. We either have to use different shortcuts or accept overriding the browser’s defaults.

Using different shortcuts seems to be considered best practice, but how useful are these shortcuts anyway? They have to be individually learned for every web app, and that’s hardly about memorizing the “keyboard shortcuts” list. Our muscles learn much more slowly than our minds. To be able to use these shortcuts as mindlessly as we use the regular application shortcuts, we need to spend a long time using the web app and those shortcuts. If we ever do get used to them that much, we’ll have trouble with the other shortcuts that most apps use, as our muscles will try to use the new ones.

Using the de facto standard keyboard shortcuts carries no such issues. They take advantage of muscle memory from day one. If we advocate that web is the new native, it means our web apps should be entitled to everything native apps are. If native editors can use Cmd+1 to go to the first tab and F1 for help, so should a web editor. When you’re running a web app, the browser environment is merely a host, like your OS. The focus is the web app. When you’re working in a web app and you press a keyboard shortcut, chances are you’re looking to interact with that app, not with the browser Chrome.

For example, I’m currently writing in WordPress’ editor. When I press Cmd+S, I expect my draft to be saved, not the browser to attempt to save the current HTML page. Would it make sense if they wanted to be polite and chose a different shortcut, like Alt+S? I would have to learn the Save shortcut all over again and I’d forever confuse the two.

Of course, it depends on how you define a web app. If we’re talking about a magazine website for example, you’re using the browser as a kind of reader. The app you’re using is still the browser, and overriding its keyboard shortcuts is bad. It’s a sometimes fine distinction, and many disagreements about this issue are basically disagreements about what constitutes a web app and how much of an application web apps are.

So, what are your thoughts? Play it safe and be polite to the host or take advantage of muscle memory?

Edit: Johnathan Snook posted these thoughts in the comments, and I thought his suggested approach is pure genius and every web UX person should read it:

On Yahoo! Mail, we have this same problem. It’s an application with many of the same affordances of a desktop application. As a result, we want to have the same usability of a desktop application—including with keyboard shortcuts. In some cases, like Cmd-P for printing, we’ll override the browser default because the browser will not have the correct output.

For something like tab selection/editing, we don’t override the defaults and instead, create alternate shortcuts for doing so.

One thing I suggest you could try is to behave somewhat like overflow areas in a web page. When you scroll with a scroll mouse or trackpad in the area, the browser will scroll that area until it reaches it’s scroll limit and then will switch to scrolling the entire page. It would be interesting to experiment with this same approach with other in-page mechanisms. For example, with tabs, I often use Cmd-Shift-[ and Cmd-Shift-] to change tabs (versus Cmd-1/2/3, etc). You could have it do so within the page until it hits its limit (first tab/last tab) and then after that, let the event fall back to the browser. For Cmd-1, have it select the first tab. If the user is already on the first tab, have it fall back to the browser.

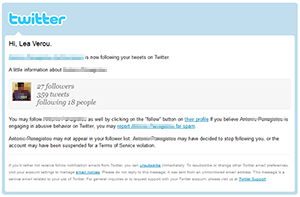

A couple hours ago, I received a notification email from

A couple hours ago, I received a notification email from