Today I tried to help a friend who is a great computer scientist, but not a JS person use a JS module he found on Github. Since for the past 6 years my day job is doing usability research & teaching at MIT, I couldn’t help but cringe at the slog that this was. Lo and behold, a pile of unnecessary error conditions, cryptic errors, and lack of proper feedback. And I don’t feel I did a good job communicating the frustration he went through in the one hour or so until he gave up.

Tag: JavaScript

ReferenceError: x is not defined?

Today for a bit of code I was writing, I needed to be able to distinguish “x is not defined” ReferenceErrors from any other error within a try...catch block and handle them differently.

Now I know what you’re thinking. Trying to figure out exactly what kind of error you have programmatically is a well-known fool’s errand. If you express a desire to engage in such a risky endeavor, any JS veteran in sight will shake their head in remembrance of their early days, but have the wisdom to refrain from trying to convince you otherwise; they know that failing will teach you what it taught them when they were young and foolish enough to attempt such a thing.

Despite writing JS for 13 years, today I was feeling adventurous. “But what if, just this once, I could get it to work? It’s a pretty standard error message! What if I tested in so many browsers that I would be confident I’ve covered all cases?”

I made a simple page on my server that just prints out the error message written in a way that would maximize older browser coverage. Armed with that, I started visiting every browser in my BrowserStack account. Here are my findings for anyone interested:

- Chrome (all versions, including mobile):

x is not defined - Firefox (all versions, including mobile):

x is not defined - Safari 4-12 :

Can't find variable: x - Edge (16 – 18):

'x' is not defined - Edge 15:

'x' is undefined - IE6-11 and Windows Phone IE:

'x' is undefined - UC Browser (all versions):

x is not defined - Samsung browser (all versions):

x is not defined - Opera Mini and Pre-Chromium Opera:

Undefined variable: x

Even if you, dear reader, are wise enough to never try and detect this error, I thought you may find the variety (or lack thereof) above interesting.

I also did a little bit of testing with a different UI language (I picked Greek), but it didn’t seem to localize the error messages. If you’re using a different UI language, please open the page above and if the message is not in English, let me know!

In the end, I decided to go ahead with it, and time will tell if it was foolish to do so. For anyone wishing to also dabble in such dangerous waters, this was my checking code:

if (e instanceof ReferenceError

&& /is (not |un)defined$|^(Can't find|Undefined) variable/.test(e.message)) {

// do stuff

}Found any cases I missed? Or perhaps you found a different ReferenceError that would erroneously match the regex above? Let me know in the comments!

One thing that’s important to note is that even if the code above is bulletproof for today’s browser landscape, the more developers that do things like this, the harder it is for browser makers to improve these error messages. However, until there’s a better way to do this, pointing fingers at developers for wanting to do perfectly reasonable things, is not the solution. This is why HTTP has status codes, so we don’t have to string match on the text. Imagine having to string match “Not Found” to figure out if a request was found or not! Similarly, many other technologies have error codes, so that different types of errors can be distinguished without resulting to flimsy string matching. I’m hoping that one day JS will also have a better way to distinguish errors more precisely than the general error categories of today, and we’ll look back to posts like this with a nostalgic smile, being so glad we don’t have to do crap like this ever again.

Reading Time: 2 minutesAlmost 11 years ago, Paul Irish posted this brilliant bookmarklet to refresh all stylesheets on the current page. Despite the amount of tools, plugins, servers to live reload that have been released over the years, I’ve always kept coming back to it. It’s incredibly elegant in its simplicity. It works everywhere: locally or remotely, on any domain and protocol. No need to set up anything, no need to alter my process in any way, no need to use a specific local server or tool. It quietly just accepts your preferences and workflow instead of trying to change them. Sure, it doesn’t automatically detect changes and reload, but in most cases, I don’t want it to.

I’ve been using this almost daily for a decade and there’s always been one thing that bothered me: It doesn’t work with iframes. If the stylesheet you’re editing is inside an iframe, tough luck. If you can open the frame in a new tab, that works, but often that’s nontrivial (e.g. the frame is dynamically generated). After dealing with this issue today once more, I thought “this is just a few lines of JS, why not fix it?”.

The first step was to get Paul’s code in a readable format, since the bookmarklet is heavily minified:

(function() {

var links = document.getElementsByTagName('link');

for (var i = 0; i < links.length; i++) {

var link = links[i];

if (link.rel.toLowerCase().match(/stylesheet/) && link.href) {

var href = link.href.replace(/(&|%5C?)forceReload=\d+/, '');

link.href = href + (href.match(/\?/) ? '&' : '?') + 'forceReload=' + (new Date().valueOf())

}

}

})()Once I did that, it became obvious to me that this could be shortened a lot; the last 10 years have been wonderful for JS evolution!

(()=>{

for (let link of Array.from(document.querySelectorAll("link[rel=stylesheet][href]"))) {

var href = new URL(link.href, location);

href.searchParams.set("forceReload", Date.now());

link.href = href;

}

})()Sure, this reduces browser support a bit (most notably it excludes IE11), but since this is a local development tool, that’s not such a big problem.

Now, let’s extend this to support iframes as well:

{

let $$ = (selector, root = document) => Array.from(root.querySelectorAll(selector));

let refresh = (document) => {

for (let link of $$("link[rel=stylesheet][href]", document)) {

let href = new URL(link.href);

href.searchParams.set("forceReload", Date.now());

link.href = href;

}

for (let iframe of $$("iframe", document)) {

iframe.contentDocument && refresh(iframe.contentDocument);

}

}

refresh();

}That’s it! Do keep in mind that this will not work with cross-origin iframes, but then again, you probably don’t expect it to in that case.

Now all we need to do to turn it into a bookmarklet is to prepend it with javascript: and minify the code. Here you go:

Refresh CSS

Hope this is useful to someone else as well 🙂

Any improvements are always welcome!

Credits

- Paul Irish, for the original bookmarklet

- Maurício Kishi, for making the iframe traversal recursive (comment)

Reading Time: 3 minutesIf you use regular expressions a lot, you probably also create them from existing strings that you first need to escape in case they contain special characters that need to be matched literally, like $ or +. Usually, a helper function is defined (hopefully this will soon change as RegExp.escape() is coming!) that basically looks like this:

var escapeRegExp = s => s.replace(/[-\/\\^$*+?.()|[\]{}]/g, "\\$&");and then regexps are created by escaping the static strings and concatenating them with the rest of the regex like this:

var regex = RegExp(escapeRegExp(start) + '([\\S\\s]+?)' + escapeRegExp(end), "gi")or, with ES6 template literals, like this:

var regex = RegExp(`${escapeRegExp(start)}([\\S\\s]+?)${escapeRegExp(end)}`, "gi")(In case you were wondering, this regex is taken directly from the Mavo source code)

Isn’t this horribly verbose? What if we could define a regex with just a template literal (`${start}([\\S\\s]+?)${end}` for the regex above) and it just worked? Well, it turns out we can! If you haven’t seen tagged template literals before, I suggest you click that MDN link and read up. Basically, you can prepend an ES6 template literal with a reference to a function and the function accepts the static parts of the string and the dynamic parts separately, allowing you to operate on them!

Reading Time: 2 minutes I just dealt with one of the weirdest bugs and thought you may find it amusing too.

I just dealt with one of the weirdest bugs and thought you may find it amusing too.

In one of my slides for my upcoming talk “Even More CSS Secrets”, I had a Mavo app on a <form>, and the app included a collection to quickly create a UI to manage pairs of values for something I wanted to calculate in one of my live demos. A Mavo collection is a repeatable HTML element with affordances to add items, delete items, move items etc. Many of these affordances are implemented via <button> elements generated by Mavo.

Normally, hitting Enter inside a text field within a collection adds a new item, as one would expect. However, I noticed that when I hit Enter inside any item, not only no item was added, but an item was being deleted, with the usual “Item deleted [Undo]” UI and everything!

At first I thought it was a bug with the part of Mavo code that adds items on Enter and deletes empty items on backspace, so I commented that out. Nope, still happening. I was already very puzzled, since I couldn’t remember any other part of the codebase that deletes items in response to keyboard events.

So, I added breakpoints on the delete(item) method of Mavo.Collection to inspect the call stack and see how execution got there. Turned out, it got there via a normal …click event on the actual delete button! What fresh hell was this? I never clicked any delete button!

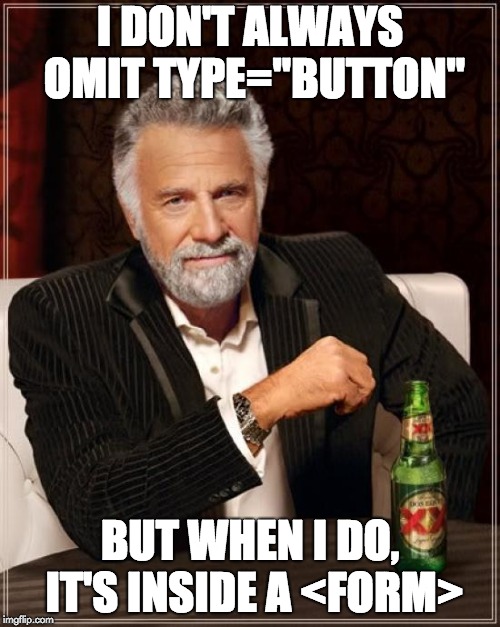

And then it dawned on me: <button> elements with no type attribute set are submit buttons by default! Quote from spec: The missing value default and invalid value default are the Submit Button state.. This makes no difference in most cases, UNLESS you’re inside a form. The delete button of the first item had been turned into the de facto default submit button just because it was the first button in that form and it had no type!

I also remembered that regardless of how you submit a form (e.g. by hitting Enter on a single-line text field) it also fires a click event on the default submit button, because people often listen to that instead of the form’s submit event. Ironically, I was cancelling the form’s submit event in my code, but it still generated that fake click event, making it even harder to track down as no form submission was actually happening.

The solution was of course to go through every part of the Mavo code that generates buttons and add type=”button” to them. I would recommend this to everyone who is writing libraries that will operate in unfamiliar HTML code. Most of the time a type-less <button> will work just fine, but when it doesn’t, things get really weird.

Reading Time: 4 minutesI often run into this issue where I want a different URL remotely and a different one locally so I can test my local changes to a library. Sure, relative URLs work a lot of the time, but are often not an option. Developing Mavo is yet another example of this: since Mavo is in a separate repo from mavo.io (its website) as well as test.mavo.io (the testsuite), I can’t just have relative URLs to it that also work remotely. I’ve been encountering this problem way too frequently pretty much since I started in web development. In this post, will describe all solutions and workarounds I’ve used over time for this, including the one I’m currently using for Mavo: Service Workers!

Reading Time: 3 minutesThose of us who use promises heavily, have often wished there was a Promise.prototype.resolve() method, that would force an existing Promise to resolve. However, for architectural reasons (throw safety), there is no such thing and probably never will be. Therefore, a Promise can only resolve or reject by calling the respective methods in its constructor:

var promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (something) {

resolve();

}

else {

reject();

}

});

However, often it is not desirable to put your entire code inside a Promise constructor so you could resolve or reject it at any point. In my latest case today, I wanted a Promise that resolved when a tree was created, so that third-party components could defer code execution until the tree was ready. However, given that plugins could be running on any hook, that meant wrapping a ton of code with the Promise constructor, which was obviously a no-go. I had come across this problem before and usually gave up and created a Promise around all the necessary code. However, this time my aversion to what this would produce got me to think even harder. What could I do to call resolve() asynchronously from outside the Promise?

A custom event? Nah, too slow for my purposes, why involve the DOM when it’s not needed?

Another Promise? Nah, that just transfers the problem.

An setInterval to repeatedly check if the tree is created? OMG, I can’t believe you just thought that Lea, ewwww, gross!

Getters and setters? Hmmm, maybe that could work! If the setter is inside the Promise constructor, then I can resolve the Promise by just setting a property!

My first iteration looked like this:

this.treeBuilt = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

Object.defineProperty(this, "_treeBuilt", {

set: value => {

if (value) {

resolve();

}

}

});

});

// Many, many lines below…

this._treeBuilt = true;However, it really bothered me that I had to define 2 properties when I only needed one. I could of course do some cleanup and delete them after the promise is resolved, but the fact that at some point in time these useless properties existed will still haunt me, and I’m sure the more OCD-prone of you know exactly what I mean. Can I do it with just one property? Turns out I can!

The main idea is realizing that the getter and the setter could be doing completely unrelated tasks. In this case, setting the property would resolve the promise and reading its value would return the promise:

var setter;

var promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setter = value => {

if (value) {

resolve();

}

};

});

Object.defineProperty(this, "treeBuilt", {

set: setter,

get: () => promise

});

// Many, many lines below…

this.treeBuilt = true;For better performance, once the promise is resolved you could even delete the dynamic property and replace it with a normal property that just points to the promise, but be careful because in that case, any future attempts to resolve the promise by setting the property will make you lose your reference to it!

I still think the code looks a bit ugly, so if you can think a more elegant solution, I’m all ears (well, eyes really)!

Update: Joseph Silber gave an interesting solution on twitter:

function defer() {

var deferred = {

promise: null,

resolve: null,

reject: null

};

deferred.promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

deferred.resolve = resolve;

deferred.reject = reject;

});

return deferred;

}

this.treeBuilt = defer();

// Many, many lines below…

this.treeBuilt.resolve();I love that this is reusable, and calling resolve() makes a lot more sense than setting something to true. However, I didn’t like that it involved a separate object (deferred) and that people using the treeBuilt property would not be able to call .then() directly on it, so I simplified it a bit to only use one Promise object:

function defer() {

var res, rej;

var promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

res = resolve;

rej = reject;

});

promise.resolve = res;

promise.reject = rej;

return promise;

}

this.treeBuilt = defer();

// Many, many lines below…

this.treeBuilt.resolve();Finally, something I like!

Markapp: A list of HTML libraries

Reading Time: < 1 minute I have often lamented how many JavaScript developers don’t realize that a large percentage of HTML & CSS authors are not comfortable writing JS, and struggle to use their libraries.

I have often lamented how many JavaScript developers don’t realize that a large percentage of HTML & CSS authors are not comfortable writing JS, and struggle to use their libraries.

To encourage libraries with HTML APIs, i.e. libraries that can be used without writing a line of JS, I made a website to list and promote them: markapp.io. The list is currently quite short, so I’m counting on you to expand it. Seen any libraries with good HTML APIs? Add them!

Copying object properties, the robust way

Reading Time: 2 minutesIf, like me, you try to avoid using heavy libraries when not needed, you must have definitely written a helper to copy properties from one object to another at some point. It’s needed so often that it’s just silly to write the same loops over and over again.

These days, most of my time is spent working on my research project at MIT, which I will hopefully reveal later this year. In that, I’m using a lightweight homegrown helper library, which I might release separately at some point as I think it has potential in its own right, for a number of reasons.

Of course, it needed to have a simple extend() method as well, to copy properties from one object to another. Let’s assume for the purposes of this article that we’re talking about shallow copying, that overwrites are allowed, and let’s omit hasOwnProperty() checks to make code easier to read.

It’s a simple task, right? Our first attempt might look like this:

$.extend = function (to, from) {

for (var property in from) {

to[property] = from[property];

}

return to;

}This works fine, until you try it on objects with accessors or other types of properties defined via Object.defineProperty() or get/set keywords. What do you do then? Our next iteration could look like this:

$.extend = function (to, from) {

for (var property in from) {

Object.defineProperty(to, property, Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(from, property));

}

return to;

}This works much better, until it fails, and it can fail pretty epically. Try this:

$.extend(document.body.style, {

backgroundColor: "red"

});Both in Chrome and Firefox, the results are super weird. Even though reading document.body.style.backgroundColor will return "red", no style will have actually been applied. In Firefox it even destroyed the native setter entirely and any future attempts to set document.body.style.backgroundColor in the console did absolutely nothing.

In contrast, the previous naïve approach worked fine for this. It’s clear that we need to somehow combine the two approaches, using Object.defineProperty() only when actually needed. But when is it actually not needed?

One obvious case is if the descriptor is undefined (such as with some native properties). Also, in simple properties, such as those in our object literal, the descriptor will be of the form {value: somevalue, writable: true, enumerable: true, configurable: true}. So, the next obvious step would be:

$.extend = function (to, from) {

var descriptor = Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(from, property);

if (descriptor && (!descriptor.writable || !descriptor.configurable || !descriptor.enumerable || descriptor.get || descriptor.set)) {

Object.defineProperty(to, property, descriptor);

}

else {

to[property] = from[property];

}

}This works perfectly, but is a little clumsy. I’ve currently left it at that, but any suggestions for making it more elegant are welcome 🙂

FWIW, I looked at jQuery’s implementation of jQuery.extend() after this, and it seems it doesn’t even handle accessors at all, unless I missed something. Time for a pull request, perhaps…

Edit: As MaxArt pointed out in the comments, there is a similar native method in ES6, Object.assign(). However, it does not deal with copying accessors, so does not deal with this problem either.

Reading Time: 3 minutesAs I pointed out in yesterday’s blog post, one of the reasons why I don’t like using jQuery is its wrapper objects. For jQuery, this was a wise decision: Back in 2006 when it was first developed, IE releases had a pretty icky memory leak bug that could be easily triggered when one added properties to elements. Oh, and we also didn’t have access to element prototypes on IE back then, so we had to add these properties manually on every element. Prototype.js attempted to go that route and the result was such a mess that they decided to change their decision in Prototype 2.0 and go with wrapper objects too. There were even long essays being written back then about how much of a monumentally bad idea it was to extend DOM elements.

The first IE release that exposed element prototypes was IE8: We got access to Node.prototype, Element.prototype and a few more. Some were mutable, some were not. On IE9, we got the full bunch, including HTMLElement.prototype and its descendants, such as HTMLParagraphElement. The memory leak bugs were mitigated in IE8 and fixed in IE9. However, we still don’t extend native DOM elements, and for good reason: collisions are still a very real risk. No library wants to add a bunch of methods on elements, it’s just bad form. It’s like being invited in someone’s house and defecating all over the floor.

But what if we could add methods to elements without the chance of collisions? (well, technically, by minimizing said chance). We could only add one property to Element.prototype, and then hang all our methods on that. E.g. if our library was called yolo and had two methods, foo() and bar(), calls to it would look like:

var element = document.querySelector(".someclass");

element.yolo.foo();

element.yolo.bar();

// or you can even chain, if you return the element in each of them!

element.yolo.foo().yolo.bar();Sure, it’s more awkward than wrapper objects, but the benefit of using native DOM elements is worth it if you ask me. Of course, YMMV.

It’s basically exactly the same thing we do with globals: We all know that adding tons of global variables is bad practice, so every library adds one global and hangs everything off of that.

However, if we try to implement something like this in the naïve way, we will find that it’s kind of hard to reference the element used from our namespaced functions:

Element.prototype.yolo = {

foo: function () {

console.log(this);

},

bar: function () { /* ... */ }

};

someElement.yolo.foo(); // Object {foo: function, bar: function}What happened here? this inside any of these functions refers to the object that they are called on, not the element that object is hanging on! We need to be a bit more clever to get around this issue.

Keep in mind that this in the object inside yolo would have access to the element we’re trying to hang these methods off of. But we’re not running any code there, so we’re not taking advantage of that. If only we could get a reference to that object’s context! However, running a function (e.g. element.yolo().foo()) would spoil our nice API.

Wait a second. We can run code on properties, via ES5 accessors! We could do something like this:

Object.defineProperty(Element.prototype, "yolo", {

get: function () {

return {

element: this,

foo: function() {

console.log(this.element);

},

bar: function() { /* ... */ }

}

},

configurable: true,

writeable: false

});

someElement.yolo.foo(); // It works! (Logs our actual element)This works, but there is a rather annoying issue here: We are generating this object and redefining our functions every single time this property is called. This is a rather bad idea for performance. Ideally, we want to generate this object once, and then return the generated object. We also don’t want every element to have its own completely separate instance of the functions we defined, we want to define these functions on a prototype, and use the wonderful JS inheritance for them, so that our library is also dynamically extensible. Luckily, there is a way to do all this too:

var Yolo = function(element) {

this.element = element;

};

Yolo.prototype = {

foo: function() {

console.log(this.element);

},

bar: function() { /* ... */ }

};

Object.defineProperty(Element.prototype, "yolo", {

get: function () {

Object.defineProperty(this, "yolo", {

value: new Yolo(this)

});

return this.yolo;

},

configurable: true,

writeable: false

});

someElement.yolo.foo(); // It works! (Logs our actual element)

// And it’s dynamically extensible too!

Yolo.prototype.baz = function(color) {

this.element.style.background = color;

};

someElement.yolo.baz("red") // Our element gets a red backgroundNote that in the above, the getter is only executed once. After that, it overwrites the yolo property with a static value: An instance of the Yolo object. Since we’re using Object.defineProperty() we also don’t run into the issue of breaking enumeration (for..in loops), since these properties have enumerable: false by default.

There is still the wart that these methods need to use this.element instead of this. We could fix this by wrapping them:

for (let method in Yolo.prototype) {

Yolo.prototype[method] = function(){

var callback = Yolo.prototype[method];

Yolo.prototype[method] = function () {

var ret = callback.apply(this.element, arguments);

// Return the element, for chainability!

return ret === undefined? this.element : ret;

}

}

}However, now you can’t dynamically add methods to Yolo.prototype and have them automatically work like the native Yolo methods in element.yolo, so it kinda hurts extensibility (of course you could still add methods that use this.element and they would work).

Thoughts?